- 1976

- 1991

- 1992

- 1993

- 1994

- 1995

- 1996

- 1997

- 1998

- 1999

- 2000

- 2001

- 2002

- 2003

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- Jerzy Srokowski - The Polish Masters of Illustration

- Rejs Krzyżaków po Ziemi obiecanej.

- Dudi on Hoża from 14th - 31 st of May 2011

- The Summer Collective Exhibition

- Tadeusz Dominik

- Jan, Piotr, Stanislaw ... Mlodozeniec

- Jacek SROKA

- 35x35x35-35 Anniversary of The Gallery of Graphics and Poster 8 th - 27th October 2011

- ANNA SOBOL WEJMAN & STANISLAW WEJMAN

- BUTENKO Pinxit

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- 2024

- 2025

Stanisław Fijalkowski

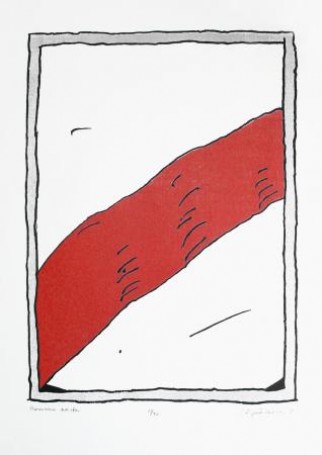

Red scarf, 1995, silkscreen on paper, 68x48cm

Stanisław Fijalkowski

Born in Zdolbunowo in Wolhynia in 1922. In 1944-45 Fijalkowski was deported to Königsberg (presently Kaliningrad), where he was pressed into forced labor. It was during Poland's occupation, a particularly difficult time in Fijalkowski's life, that he undertook his first creative explorations as an artist. These efforts were entirely independent, unguided by anyone. He did not find time for systematic study in painting until after the war. Between 1946 and 1951 he attended the State Higher School of the Fine Arts in Lodz, where he was a student of Wladyslaw Strzeminski and Stefan Wegner, though he had Ludwik Tyrowicz as his thesis promoter. From among his teachers, Fijalkowski most readily names Strzeminski as an influence, perhaps because he later worked under him as an assistant (the artist taught at his alma mater from 1947-1993, becoming a full professor in 1983). He was an important presence within the group of educators who shaped the school in Lodz (known today as the Academy of Fine Arts). He also guest lectured for brief periods at a series of foreign art schools, among them the schools in Mons (1978, 1982) and Marburg (1990). He taught classes at Geissen University throughout the 1989/90 academic year. Fijalkowski began his career as an independent artist by rebelling against his master, creating works that possess a clear link to those of the Impressionists. He made an effort to delineate his own, individual creative path by taking a clear position towards tradition and the achievements of the masters, particularly Strzeminski. Towards the end of the 1950s he proceeded along a course typical of Polish painters fascinated with Informel, taking an interest in the symbolic meanings inherent in abstract expressive means. He believed that "unreal" shapes are justified in paintings when they are saturated with meaning. Years later, in writing a brief curriculum vitae, the artist added that it was approximately at this time that "...apart from interpreting reality within an esoteric dimension, there appeared [in his paintings] the need to organize the esoteric meanings inherent in form." Fijalkowski admits that the shape of his art was to a significant degree determined by the writings of Kandinsky (whose "Über das Geistige in der Kunst" Fijalkowski translated and published in Poland) and Mondrian, and by his interest in Surrealism. These two branches of 20th century art unexpectedly combined in Fijalkowski's art to produce surprising results. At the turn of the 1950s and 60s Fijalkowski continued to search and experiment, using the canvas as a plane on which to juxtapose the essentials of Strzeminski's ordering principles with something within the realm of Surrealism that was stripped of direct metaphorical meanings and allusions. The change that occurred in his paintings consisted primarily of a gradual abandonment of pure, literally allusive form. In the painter's own words, during this time of reflection, "I attempted more boldly to create forms that did not impose a single meaning, leaving viewers fully free to access the ingredients of their personalities, that may be unconscious or repressed but are absolutely truthful. I sought, and continue to strive, to create form that is only the beginning of the work as generated by the viewer, each time in a new shape..." In Fijalkowski's works, "form" is more open the more it is modest, efficient, insinuated. Most of his compositions are constructed based on a simple set of principles whereby an almost uniformly colored background is filled in with elements that resemble geometric figures but have rounded corners and soft edges, generating a poetic mood. The decisive hues used for the backgrounds of these canvasses, however, decidedly modifies their function and meaning - at times, the background dominates the entirety of the image, becoming an abyss, a void that draws into its interior large, spinning wheels, ellipsoidal forms, or diagonal lines that cut across the painting. One could expect this repetition of forms to render both Fijalkowski's painted works and his graphic art pieces tiring (the artist has been equally active in both areas, working in cycles, though the subjects undertaken often appeared in compositions created in various techniques). This impression is only reinforced by the artist's palette, which was restricted; he willingly used "undecided colors" that were muted, cool, and only at times broken up with ribbons of categorical black. But Fijalkowski was able to extract a tension out of this monotony and uniformity, in a manner that usually remains unfathomable to the viewer. Likewise, the meanings the artist assigns to these puzzling arrangements remain largely a mystery. In the end, it is the erudition of viewers, their rooting in culture and awareness of contemporary art, finally their intuition that determine their ability to enter into a dialogue with the artist and his work. This dialogue is easier to establish in the case of pieces that contain "objective" suggestions and clear references, for instance to Christian iconography. It is more difficult in the case of abstract compositions like WAWOZY / RAVINES, WARIACJE NA TEMAT LICZBY CZTERY / VARIATIONS ON THE NUMBER FOUR, STUDIA TALMUDYCZNE / TALMUDIC STUDIES, or works like AUTOSTRADY / HIGHWAYS that derive from the artist's personal experiences. Nevertheless, Fijalkowski's paintings are charming, even to the uninitiated viewer, for the ascetic painting techniques used, for a compactness deriving from the skillful balancing of emotions and intellect, intuition and conscious thought, individual expression and universal meanings - something very much in line with the artist's own expectations. The parallel existence and synthesis of the concrete forms of the works with the mystery of their message - a synthesis of that which is external to the works with that which is internal - prevents his oeuvre from being perceived as over-aestheticized. In the end, his work seems to be the result of a search for harmony, for a principle that would impose order on the lack of direction felt by contemporary man. The artist achieves this aim through a distinct painterly language that sets his art apart from that of other artists, rendering it exceptional and original, not only, it seems, when compared to the work of other Polish artists. Stanislaw Fijalkowski is chairman of the Polish section of the XYLON International Association of Wood-Engravers and has been a vice president of this body's International Board since 1990. Between 1974 and 1979 he was the vice president of the Polish AIAP Committee (Association Internationale des Arts Plastiques). He is a member of the European Academy of Arts and Sciences in Salzburg and the Royal Belgian Academy of Sciences, Literature, and Fine Arts in Brussels. The artist represented Poland at the biennales in Sao Paulo (1969) and Venice (1972). In 1977 he received the Cyprian Kamil Norwid Art Criticism Prize and was awarded the prestigious Jan Cybis Prize in 1990. He has also received numerous domestic and international awards at a number of exhibitions, including the Graphic Art Biennale in Krakow (1968 and 1970), the Bianco e Nero Exhibition in Lugano (1972), and the Graphic Art Biennale in Lubliana (1977). In celebration of the artist's 70th birthday, the National Museum in Poznan is planning a retrospective of Fijalkowski's work for the year 2002.

Your message has been sent. Thank you!

An error occured. Please try again.